Corn Sweat

The best our modern plant men have been able to do is improve the yield

Last summer, while revolving around the sun in time with Hal Borland’s Book of Days, I dogeared a page about corn. Well, I dogeared a lot of pages. He’s that kind of writer. But only one about corn.

Corn…is a botanical achievement that modern man has never been able to duplicate. Somewhere far back in the mists the Indians of Central America created it from a native grass, by selective breeding and cross-breeding. We find cobs and miniature ears in ancient caves in our own Southwest, and archaeologists have traced the grain far back among the Aztecs and their forerunners. But no one has ever succeeded in breeding anything like even the primitive corn in the ancient caves from the known plants of the world. The best our modern plant men have been able to do is improve the yield or increase the size of the ears or alter the flavor of the kernels.

And I hope they never break that long-standing secret of those “primitive” Indians who first created an ear of corn.

I marked that page last summer because it sent me spiraling thinking about the uses to which we are putting our human ingenuity here in the present, which seem to be almost universally regressive in nature: it’s no secret that funding for the arts and sciences is being not so much slashed as eradicated, with the real money and social investment now going exclusively to the internet slop creation machine, surveillance tech, and ever-more expensive weaponry. (Incidentally, our other main site of innovation seems to be in corn syrup-based treats, which frankly have never tasted better.)

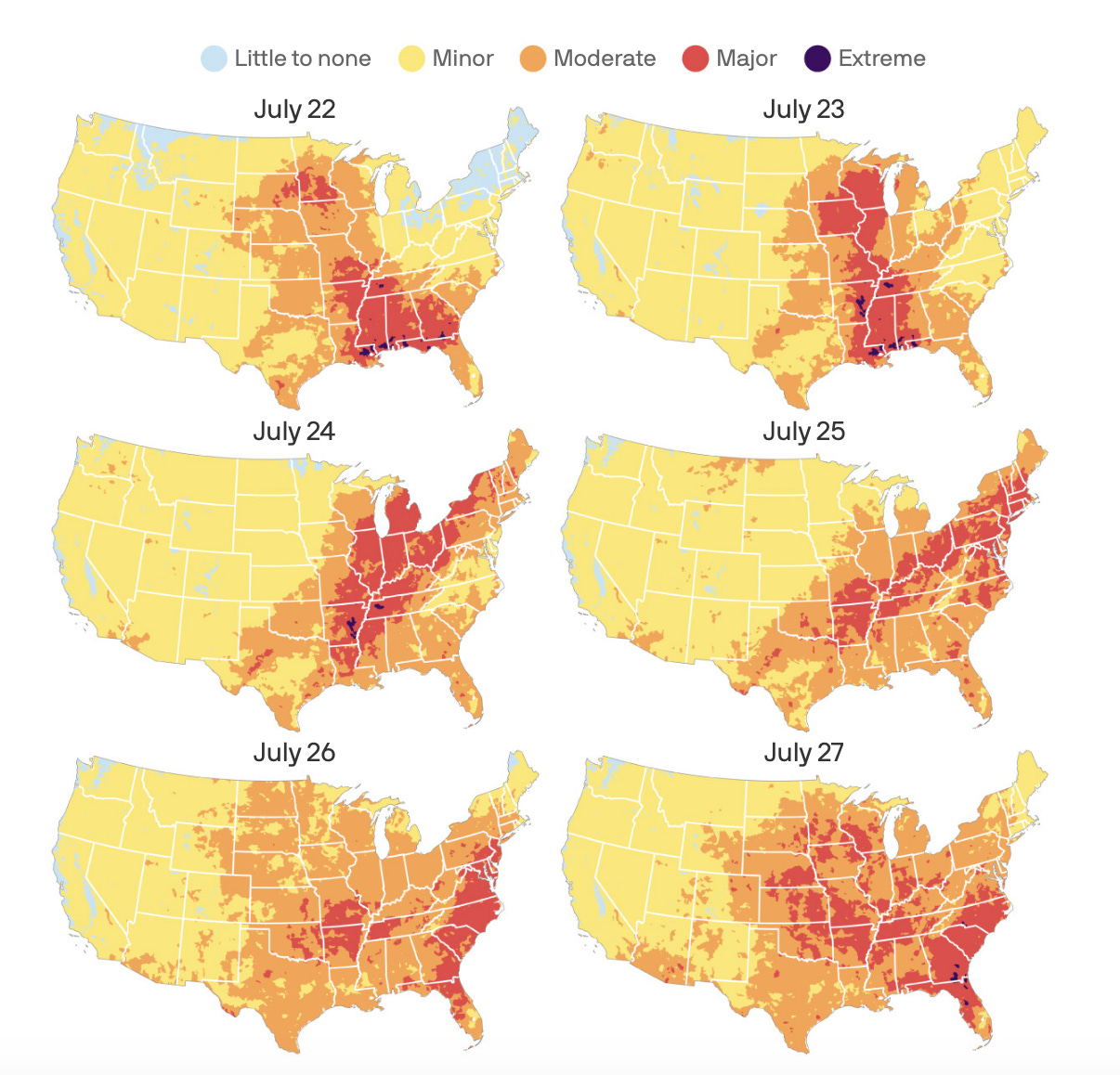

But I’m thinking about that page this summer because I’m thinking about corn itself, because this week corn has contributed to making the Midwest, where I live, feel close to unlivable. This is thanks to “corn sweat,” the phenomenon whereby evapotranspiration from crops drives up the humidity during periods of intense heat. Borland was right to see corn as something of a miracle, but that hasn’t exempted it from being tortured, Orc-like, from something beautiful into a heinous, world-wasting force.

Maybe you know all of this already, maybe this doesn’t help to know. Less than twenty percent of the corn grown in the U.S. is turned into human food. More than eighty percent is processed into ethanol fuel or fed to livestock. We spend three billion dollars a year to subsidize farmers using ninety million acres to grow a single type of plant that we mostly use to inject cheap fuel into cars and cows, an ecocidal triumvirate on which the entire world economy depends. Makes you wonder what the point of the world economy is if there’ll soon be no world to make use of it. You buy the logic of the spiral long enough it’s hard to remember it doesn’t have to be that way. Like those photos you see sometimes of whitetail bucks or moose that get so caught up fighting they lock their antlers together and both die of hunger. Something like that.

There are no shortcuts to power, to revolution, to winning a world fit for humans and other life. Still I find myself dreaming lately of some great fire leaving alone, for once, the parched and beautiful west and instead sweeping down through the monocultured fields where grow the yellow and green stalks of living coal that strip bare the dirt and make even the sky sweat and boil.

We did the impossible once, turned grass to food through generations of daring and careful stewardship. And in our infinite wisdom we’ve totally botched it, grown the corn as thick and useless and destructive as the grass it once was that now adorns our lawns. I think of the people of Gaza reduced to eating grass once again and how heinous it feels to live in a country where we grow food crops to burn in the engines of cars while we starve a whole nation on the other side of the world and feign surprise that the guns we’re firing contain bullets. The man shot dead carrying flour to his family is my brother in the way that the demons doing these things to us will never be, and I am powerless to help him. The skeletal child denied formula for so long her body eats itself is my child, and I cannot feed her.

I dream about what might come after the fire, the slow and scraggly climb back out of the eroded monoculture. First the weeds pushing forth from the burned and desolate ash, the shrubs and vines, the little trees in long succession. The forests themselves, left long enough.

We wrought miracles from the earth once. I cling to that on the bad days. The pink bells of the fireweed and their silent chime in the hot wind above the burn.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

One way I try to resist this situation is growing old, indigenous crops. I'm so grateful for Native Seed S.E.A.R.C.H. providing this option.

"We did the impossible once, turned grass to food through generations of daring and careful stewardship. And in our infinite wisdom we’ve totally botched it, grown the corn as thick and useless and destructive as the grass it once was that now adorns our lawns. I think of the people of Gaza reduced to eating grass once again and how heinous it feels to live in a country where we grow food crops to burn in the engines of cars while we starve a whole nation on the other side of the world and feign surprise that the guns we’re firing contain bullets. The man shot dead carrying flour to his family is my brother in the way that the demons doing these things to us will never be, and I am powerless to help him. The skeletal child denied formula for so long her body eats itself is my child, and I cannot feed her."

I felt that.

Thank you for your writing.