Not Far From The Buried Iron

Our hunger reveals the nature of our lives and deaths

I’ve been rereading Moby-Dick this month. I did so in August of 2015 and again in August of 2020 and see no reason not to keep doing so in every fifth August from now until the end of time. There are very good reasons the canon has been reevaluated in recent years, with a scrutinous eye toward its maleness, its whiteness and Eurocentrism, and I’m glad of it. But some classics are classics for good reason.

For my money, Melville’s magnum opus is The Great American Novel. This is graspable even for those who only know Moby-Dick through cultural osmosis: the metaphorically-dense, ill-fated and reckless pursuit of something rare and terrifying, for revenge and for glory, is something we can all recognize from any number of eras of our national history (or national mythology). It is also a deeply funny book, which you may not know if you’ve only ever heard about Ahab and his ivory leg, or about the insane digressions in which Ishmael attempts to classify every whale on Earth or to retrofit Physeter macrocephalus onto every sea monster myth in the history of the world. Ishmael is a gallows humorist first and foremost, and Melville’s own wit shines through on every page.

But even more than the pursuit of the eponymous whale, even more than the humor, even more than the author’s attempts at something like real naturalism (which has at least as many instances of astonishing accuracy as it does laughable inaccuracy), what seems most fundamentally Great and American about the novel is a single scene played out over ten pages in Chapter 81, “The Pequod Meets The Virgin.” I didn’t remember this scene at all from previous reads and was so struck by it last night that I had to close the book. I lay there in bed for some time just processing. (A good case for reading and rereading great books: there’s always more to glean from them.)

In it, the whalers of the two vessels named above compete in the pursuit of a single sperm whale, a “huge, humped old bull” with a damaged fin and “unusual yellowish incrustations overgrowing him” who can’t swim as fast as the pod he’s protecting. The hunt that unfolds is devastating, for Ishmael can’t help but narrate with great sympathy even as he rows hard so that he might be among the crew who “darts” the whale:

His spout was short, slow, and laborious; coming forth with a choking sort of gush, and spending itself in torn shreds, followed by strange subterranean commotions in him, which seemed to have egress at his other buried extremity, causing the waters behind him to upbubble.

“Who’s got some paregoric?” said Stubb, “he has the stomachache, I’m afraid.”

(Humor and tragedy cleave together on every page of this book. Cruelty, too, lurking just beneath it all.)

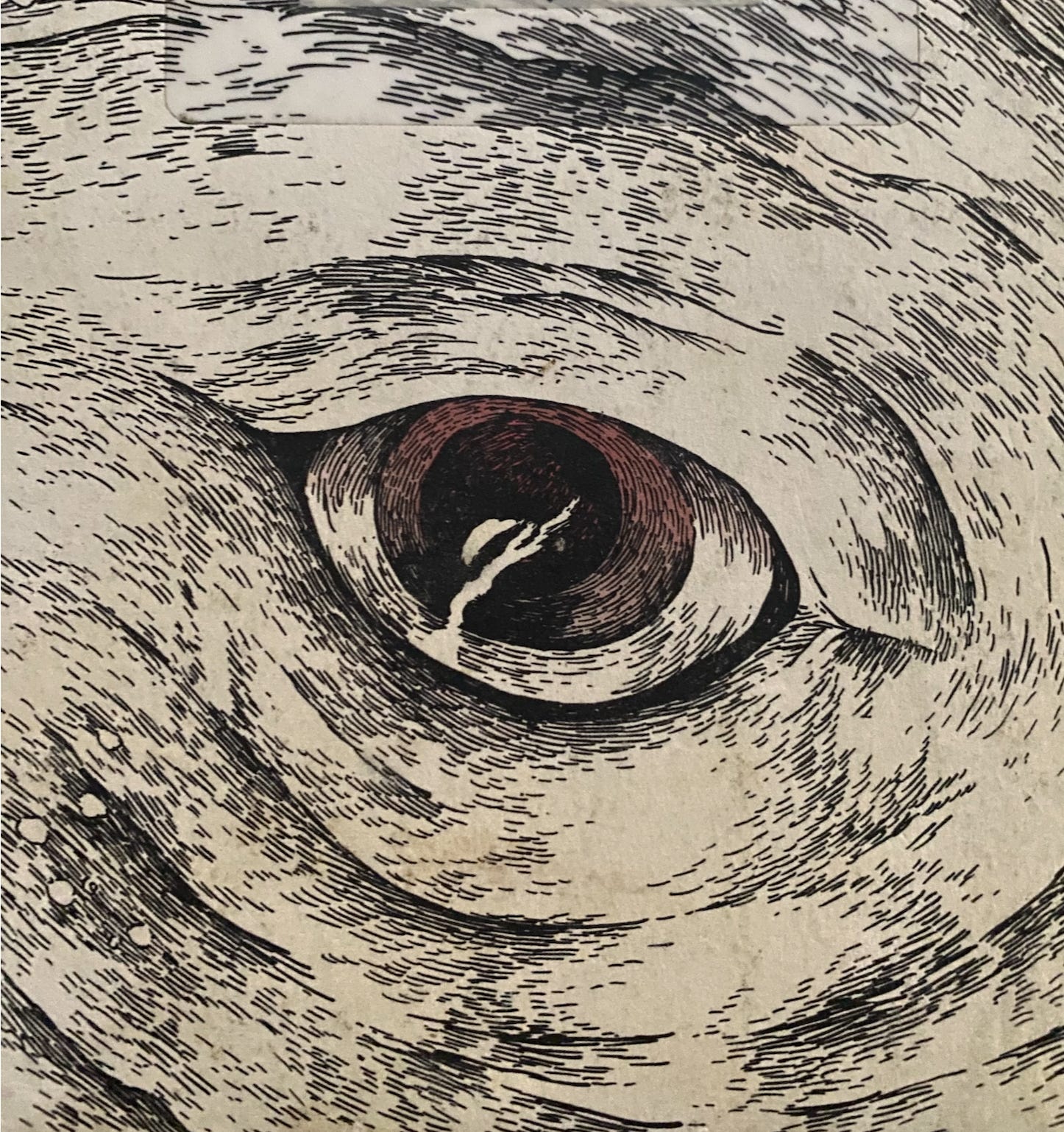

All three Pequod boats eventually get their harpoons into the struggling whale, and when he resurfaces near death at the ends of their lines, the intimate tragedy becomes an existential one:

As the boats now more closely surrounded him, the whole upper part of his form, with much of it that is ordinarily submerged, was plainly revealed. His eyes, or rather the places where his eyes had been, were beheld. As strange misgrown masses gather in the knotholes of the noblest oaks when prostrate, so from the points which the whale’s eyes had once occupied, now protruded blind bulbs, horribly pitiable to see. But pity there was none. For all his old age, and his one arm, and his blind eyes, he must die the death and be murdered, in order to light the gay bridals and other merrymakings of men, and also to illuminate the solemn churches that preach unconditional inoffensiveness by all to all. Still rolling in his blood, at last he partially disclosed a strangely discolored bunch or protuberance, the size of a bushel, low down on the flank.

“A nice spot,” cried Flask; “just let me prick him there once.”

“Avast!” cried Starbuck, “there's no need of that!”

But humane Starbuck was too late. At the instant of the dart an ulcerous jet shot from this cruel wound, and goaded by it into more than sufferable anguish, the whale now spouting thick blood, with swift fury blindly darted at the craft, bespattering them and their glorying crews all over with showers of gore, capsizing Flask's boat and marring the bows.

Not just a killing, then, but a killing without dignity. And still the injuries deepen, even once the whale has spent his life in that last horrifying gush of blood:

It so chanced that almost upon first cutting into him with the spade, the entire length of a corroded harpoon was found imbedded in his flesh, on the lower part of the bunch before described. But as the stumps of harpoons are frequently found in the dead bodies of captured whales, with the flesh perfectly healed around them, and no prominence of any kind to denote their place; therefore, there must needs have been some other unknown reason in the present case fully to account for the ulceration alluded to. But still more curious was the fact of a lance-head of stone being found in him, not far from the buried iron, the flesh perfectly firm about it. Who had darted that stone lance? And when? It might have been darted by some Nor' West Indian long before America was discovered.

What other marvels might have been rummaged out of this monstrous cabinet there is no telling. But a sudden stop was put to further discoveries, by the ship's being unprecedentedly dragged over sideways to the sea, owing to the body's immensely increasing tendency to sink.

Yes: the men of the Pequod expend themselves all day in hunting and brutally killing a whale older than anything they would recognize as their own nation, older than the European conquest of the Americas, and are then forced to cut the entire carcass loose without extracting a single barrel of oil or an ounce of ambergris. An utter and senseless waste, in other words, carried out by men with just enough knowledge and skill for violence but not nearly enough to make anything lasting of it. What, truly, could be more American than that?

And because I am thinking about American violence—I am rarely not thinking about American violence—I can’t help but think about our attitudes and definitions of that term, and how slippery they become. The United States was a willing party to the worldwide moratorium on whaling imposed by the International Whaling Commission, putting an end to our own barbarous complicity in the slaying of these beautiful and intelligent beings with whom we share the planet. But of course we have no such compunctions about imposing violent regimes on our fellow man, be it the rapid violence of warfare or the slow violence of sanctions and starvation, or the wretched combination of both we have unleashed in Palestine, among other places.

Here, too, a great and tragic irony: Moby-Dick’s main inspiration was the 1820 sinking of the whaleship Essex after it was rammed twice in the open Pacific by an 85-foot bull sperm whale. The Essex crew took to the lifeboats, and, dreading the “cannibals” they might encounter in the Society and Marquesas Islands, attempted to sail a much less direct route to the western coast of South America. Desperate and starving, they began to eat the bodies of their crewmates who had already died of hunger, and in one boat eventually drew lots for a sacrifice so that the others might eat him and so live. I make no moral judgments of the desperate but I can’t help but wonder how much suffering we might be spared if we could recognize that what we fear most in others is something that already lives within ourselves. I think about what we know comes to Americans who suffer great hunger and privation, and about how we hear no such stories from Gaza, and I wonder what that says not about the way we die but about the way that we live. I wonder. I wonder.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

PPS - An even better way to make use of your spare scratch this week would be to send it to people in Gaza. Two people I’ve been donating to when I can are Nader and Amjad. If it matters, given the scammy nature of the world, I’ve seen reliable verification from people I trust that these two fundraisers are real and urgent.