On Punishment

I'm opting out

The semester just wrapped up, and with it came the same question I have to ask myself at the end of every semester, when final projects are due and grades are entered: will my students benefit more from learning a hard lesson or from receiving more grace than could reasonably be expected?

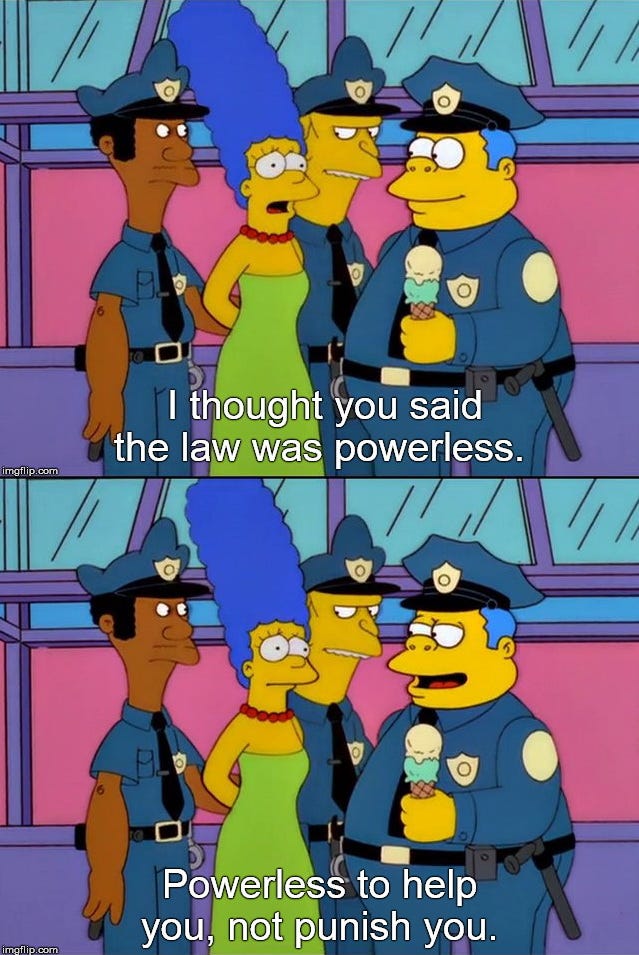

It’s not an exact binary, and sometimes the answer is “both,” and sometimes I don’t have a good answer at all. But I do know that, on the whole, our entire society seems constructed to be good at punishing people, and little else. To punish them for being anything other than rich, white, straight, and male, especially. I’m not breaking news here. But if you take stock of how just about anything works in this country it’s hard not to see how many hard, cruel layers there are to just about every system, process, and norm we’ve got. And as products of a system that can do nothing but punish, we in turn love to punish each other. We love to suffer minor indignities and inconveniences so that we might have an opportunity to work it all out on someone else.

My wife and I were talking about this the other night. She moonlights as a high school lacrosse coach and so witnesses a lot of emotional escalation: coaches, players, and referees alike all just sort of screaming at each other all the time. There is a boiling, seething resentment lurking about a millimeter below the skin of every American, and we all seem desperate to just take it out on each other at all times, from the President on down.

This is what I keep coming back to, when I make this decision each semester: that I no longer care to participate in the paradigm of punishment upon which the whole world seems to depend. I’ve had enough of it.

You can yell at your dog for “misbehaving,” but that’s not going to teach the dog anything different. Yet I see people yelling at their dogs all the time—which of course is their failure, not the animal’s. The government can erect byzantine structures of drug testing and means testing and slash funding to try to force the destitute back to work—and all that ever happens is further immiseration, further destitution, the further erosion of human dignity. I could fail a student in May for missing a single deadline that seemed so reasonable to both of us back in January—and, like the bureaucrat, I would never need to bother myself with what became of them afterward. Somebody else’s problem, once I’ve washed my hands of it all.

Refusing to do so seems hopelessly naive, I imagine. It certainly feels that way to me sometimes, and I’m the one making the choice. But I never know if the student is ignoring my emails and skipping my class because they’re a shithead teenager who thinks they have better things to do or because they’re in some profound crisis and in need, more than anything, of a little help. I never know, and that’s the point: I have to make my choices anyway.1 I am trying to destroy the cop inside my head, which means learning to let go of the fear that someone else—in this case, a teenager under my supervision and care—might get one over on me.

Plus—and again, I have to constantly remind myself of this—even if the kid is just being a shithead, they’re a shithead who has already been failed by countless adults and systems by the time they hit my classroom. When I taught community college it was the more obvious culprits: poverty, jail, discrimination, police, hunger. But even my more comfortable university students are learning in real time just how bad a hand they’ve been dealt. Some students miss my emails because they don’t know how to check their email. No one’s thought to check to see if they know how to do that! Students struggle to analyze texts and write about them because they weren’t required to do that to graduate high school. They don’t have to read whole novels anymore! Students use AI to write papers for my class despite the explicit ban I’ve placed on that practice because AI has been given the greenlight by companies, advertisers, and governments! My own institution has rolled out a GPT to “assist” students and instructors with their workload!

So I say fuck it, basically. I wrestle and worry over the idea that my extension of grace might someday cross the line into devaluing the hard work of students who do everything they’re supposed to do without my intervention, but I also take enough pride in my own work to feel comfortable asserting a difference between “freedom from punishment” and “freedom from consequences.” One of the required pedagogical trainings I took last year was geared toward learning to become a warm demander, which is to say an instructor that respects their students by holding them to high standards while still making room to see them as whole people and to make choices about how to deal with them accordingly. It doesn’t come easily to me, especially the demander half, but it feels worth doing.

Case in point: I had a student this semester who had a ton of final drafts overdue. (We have four major essays for the course; there are separate “rough” and “revised” draft deadlines; they need a mark of “complete” in every category of the rubric to get a passing score for each essay.) Most of the feedback I had given them on their early drafts was to the effect that a) they hadn’t followed the prompts and b) the writing was clearly AI-generated and not their own, both of which they would need to fix if they wanted to earn a passing grade. In an effort to keep them (and others) from failing I extended the final deadlines twice, accepting old work that should’ve been done and dusted in January and February as well as a late draft of the final paper. And this student continued to turn in nothing but AI-generated drafts that didn’t really respond to my prompts. That student, having exhausted all available avenues of grace, got to learn a hard lesson.

I don’t have all the answers here, obviously. In fact this new paradigm I’m working through drives me nuts, a lot of the time. I’m not sure how else to square the requirements of academic grading with the framework through which I teach writing, which is one that necessitates drafting and revision and iteration until the ideas within are clear and complete. That takes time, and it certainly won’t look the same for every student.

And, well, at least through this approach I get to opt out of something I hate. This is surely a nation of scammers and fraudsters and hucksters but I think I have it in me to give teenagers the benefit of the doubt. Despite my best efforts I still have a lot of poison to draw out of myself and this feels like one good way to do it.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

Well, sometimes I know, at least afterward, because at least once a semester I get an email from a kid saying that they appreciated that one last shot, because xyz terrible thing had been going on in their life and they couldn’t manage it all at once. Good enough for me.

I gave up on searching out all signs of possible student misconduct long ago -- scouring every paper for familiar phrases, peering over shoulders, and searching through students' social media pages to see if their excused absences lined up with their real life activities demanded so much of me, and the moral highground of having caught someone in a lie was really the only thing either of us gained from it. Now, when there is a possibility of a student having cheated, I tell myself that it was their choice to not reap the full educational benefits of the assignments that I've given them, and that they might have their reasons for preferring a quick passing score over the risk of facing scrutiny for their real work.

Ultimately it is on me to convince my students that we're both here because we are invested in their growth, and that my classroom is one where it's safe to show their imperfect work, to not know things, and to sometimes fail. I can't reach everyone, and I don't take it personally when they have other priorities. But moving toward "warm demand" sounds like a good aspiration. The popularity of AI-written papers reflects a profound cynicism in the value of institutionalized education, and it's often well-deserved. Most of our efforts in this world are unrewarded and unremarked upon. If there's anything I can do to make my students feel like it is worth trying, worth believing in the pursuit of the goal and staying present in its pursuit, I want to be able to do it.

Thanks for writing. I just had a student that I'd resigned to failing take me completely by surprising by turning in *8* missing essays and a final project that are of more than serviceable quality today. No signs of AI. Sometimes, thank god, our well-earned cynicism is wrong. Moments like that are why we keep believing in the possibility of one another.

I was watching Scared Straight once, trying to reconcile the obviously earnest desire of the convict to help the young man avoid mistakes in life with the transparent ineffectiveness of the screaming and the fear. "This is silly," I thought. "you cannot hurt someone into being a better person." and once I put it like that I could see it everywhere. people and their children, international sanctions. it's all just pain. kudos to you for reflection and trying something different.