We Are In The Midst Of An Almost Constant Caretaking

Lessons from ancient burial mounds

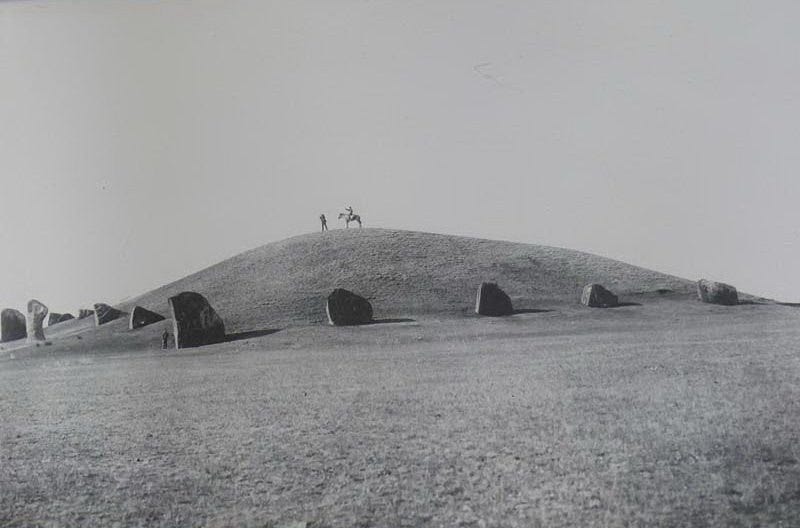

About six thousand years ago, as far as we can tell, societies on the Eurasian steppe began constructing what we call kurgans. A kurgan is a type of tumulus: a large burial mound raised over a gravesite. A manmade hill, from the outside, although the innards can be quite complex. (The barrows in which Frodo Baggins and the other Hobbits get trapped in the early days of their flight from the Shire are another type of of tumulus.)

The Indo-Europeans, and their successors ranging from the Black Sea to Scandinavia, built these massive earthworks to honor their celebrated dead. Sometimes just one elite corpse would command an entire kurgan, sometimes whole families or a collection of dead warriors from the same army. They might be filled with weaponry, with treasures, with the warriors’ horses. All the things they might want and need in their journey to the afterlife.

Early kurgans mostly seem to contain men, although archaeologists did notice a shift in the gender balance within excavated sites as time went on and the practice spread westward. The legend of the Amazons, the formidable woman-only society of warriors, likely has its origins in ancient Sarmatia (near the present-day Russia-Kazakhstan border), where a kurgan containing more than 150 women, some in full battle dress bearing fatal wounds, was excavated in the 1990s.

Kurgans fascinate me for the same reasons other ancient practices and structures do: I can’t stop thinking about what visions of the future the people who created them might have had. Did they have any inkling that a society so far in the future as to inhabit a materially different reality from their own would still be talking about them, examining them, learning from them? Could they have guessed that we would be using their dead to learn about their living?

What’s more, I delight in what they can’t possibly have predicted or known, the impacts on our modern world that they could not have conceived of.1 To wit:

The researchers pointed out that in agricultural landscapes (typical of the western steppe regions in Eastern and Central Europe) where grasslands were severely affected and almost completely disappeared due to landscape transformation, almost half of the kurgans still preserve the remnants of steppe grasslands. In such landscapes, kurgans can act as biodiverse terrestrial habitat islands, which provide ‘safe havens’ for grassland biota.

As their former studies showed, even the smallest kurgans embedded in extensive arable lands can provide habitat for many red-listed plant species that otherwise disappeared from the landscape. In less intensively used landscapes where at least part of the former grassland stands remained, kurgans can function as stepping stones that can connect fragmented populations of grassland biota and also represent biodiversity hotspots.

I first learned about kurgans on Twitter (I will never call it “X”), in this thread that describes their incidental defensive function beautifully.

Kurgans honor and preserve the lives of dead people and dead societies while acting as a bulwark against the eradication of other living things. I find that impossibly moving, just as I find cave paintings and petroglyphs moving for all their magic and endurance. “We were here,” they all say, the ancient art and the burial mounds. “And that still matters, because there is a you to bear witness to them.”

Reality might be different now, and we might be less certain that a future even exists than the people of previous eras were. But some things have not changed in all of time’s long slow march. We still honor the dead so that we might bring comfort to the living. We still build things in the hope that we will be remembered in some age beyond our reckoning, or at least for a little while after we’re gone. We worry about the future and we make things to keep records of the past, to make sense of who we were and what we’d like to remember. Raised mounds and petroglyphs. Grafitti and statues. Books. Internet newsletters, maybe. And we care for each other, beyond all utility or reason, as the cases of Shanidar 1, the Manot Cave Boy, Burial 9, Windover Boy, and Romito 2 demonstrate—in direct defiance of the quasi-religious American belief in rugged individualism.

The case…is that of a profoundly ill young man who lived 4,000 years ago in what is now northern Vietnam and was buried, as were others in his culture, at a site known as Man Bac.

Almost all the other skeletons at the site, south of Hanoi and about 15 miles from the coast, lie straight. Burial 9, as both the remains and the once living person are known, was laid to rest curled in the fetal position…His fused vertebrae, weak bones and other evidence suggested that he lies in death as he did in life, bent and crippled by disease.

They gathered that he became paralyzed from the waist down before adolescence, the result of a congenital disease known as Klippel-Feil syndrome. He had little, if any, use of his arms and could not have fed himself or kept himself clean.

…They concluded that the people around him who had no metal and lived by fishing, hunting and raising barely domesticated pigs, took the time and care to tend to his every need.

That we deserve better, that we desperately need a rapid reordering of our society and its productive enterprises so that we might stave off dragging the entire global ecosystem to hell with us, is no secret. But what is harder to remember is that outside of this exploitative, competitive nightmare that we have been taught is the only true manner of being, we have always been good at taking care of each other. We’ve even been good at taking care of the planet, whether we meant to or not. Whether we could plan something so beautiful as our burial mounds becoming ecological oases or not.

Ross Gay, in his Book of Delights, says:

“No man is an Island,” John Donne famously wrote. But I wonder if he’d allow that one might be a kurgan. If we feel ourselves to be alone, it is only because we have been made to forget that our highest purpose is the care and defense of all the living, and all the living yet to come. Times have changed, but the love and care we are capable of showing each other has not. And perhaps in remembering that—in reprioritizing our lives to better understand the importance of we and us—we might find it within ourselves to endure and survive whatever comes next.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

If one were so inclined this coincidence might prove really instructive: that the deaths of a whole lot of elite members of society eventually provided stepping stones toward staving off an ecological disaster.