Wonder Is A Skill

Cultivating vegetables and an imagination require the same sort of habits.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the relationship between the kinds of things I was reading as a kid and the adult I have so inescapably become. There are some pessimistic reasons for this, which I’ll explain shortly, but the most recent revelations have been the positive sort.

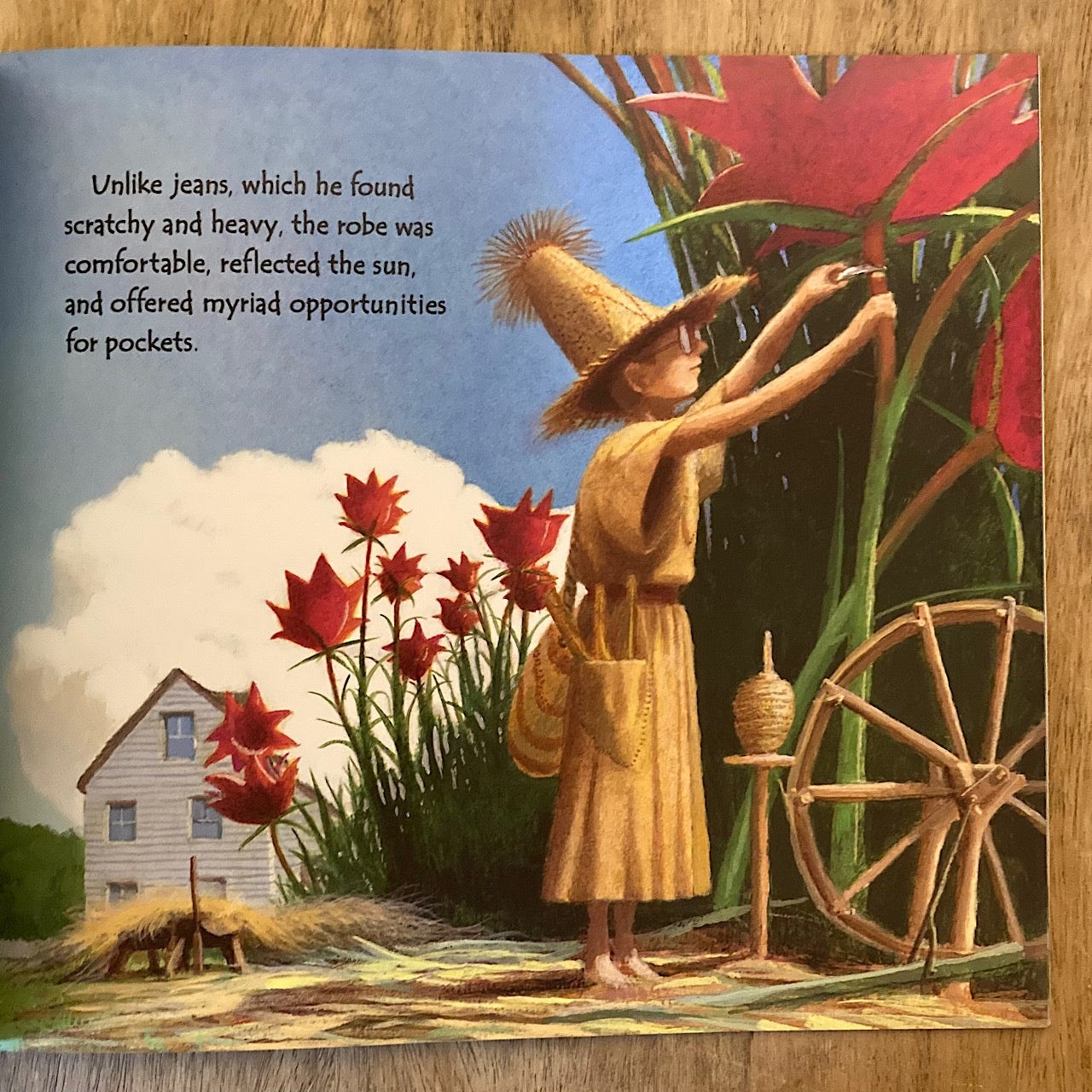

I remember, in particular, one by Paul Fleischman called Weslandia. This book tells the story of an outcast boy, Wesley, who discovers a strange plant growing in his yard and spends a summer nourishing and cultivating it. The plant, which he calls swist, grows with such fecundity that it becomes the basis for Wesley’s own micro-nation: he eats its fruit, builds his own network of infrastructure using its stems and vines, weaves his own clothes, and develops a new language and writing system after processing the swist juice into ink.

It’s a perfect book in many ways, and you can probably see where I’m going here. It’s a triumphant and beautifully illustrated story, one that a lot of kids could see themselves in. And in deftly walking the tightrope between the believable and the fantastical, it’s an expansive book, one that invites kids to go out into the world and find the richness in it, even if they don’t want to engage with the finer points of nation-building.

Anyway I’ve written before, possibly too many times (though I never know how many people reading are new here), about the fact that my wife and I moved to Detroit in the hopes of living more communally with a few of our friends. The linchpin of this project is the work of growing our own food, as much of it as we can. And while we don’t yet own a shared property upon which to grow all this food, we’ve been getting our reps in the interim by developing a shared garden in the backyard of a house owned by two of our friends and lived in by two others.

We’re learning a lot, doing this. That you can plant marigolds between your tomatoes to defend against root-rotting nematodes in the soil. That a border of anise hyssop can help combat the cabbage moths that put holes in all the brassica leaves. That besides watering and weeding and staking, even a small backyard garden requires mapping and planning and rounds of revisions to get everything in a place where it can thrive, and that this is a lot less fun than getting your hands in the dirt. That getting your hands in the dirt is a lot of fun. (Well, that one I knew.) That pulling and eating a fresh raw radish that you grew from seed is a joy worth looking forward to each May.

It’s also inspired us to think back beyond the scientific method to the times when there was little distance between science and magic. Appropriating some old folk wisdom, we planted a few eggs deep in the soil in our tomato beds. Before anyone had a name for calcium or nitrogen, they had rituals like this one, laying eggs or fish beneath their crops to increase their yields. There are so few opportunities to reconnect with who we were so long ago that I jumped at the chance to try this one. I have no data and will likely never collect any; the point, to me, is to do what others used to do and so live with a little more faith in magic than I used to.

Obviously it’s possible that I still might have ended up this way without that single book I read some twenty-five years ago. But I think it’s very likely that the amalgamation of all the books I was reading in those days have profoundly influenced my interests in and about the world. I’ve detailed—again, maybe too many times—my belief that I would not have become a dedicated backpacker without wandering Snufkin from the Moomin series or the adventuring storytellers of Redwall. Both get a shoutout in a lovely recent essay from Katherine Rundell titled “Why Children’s Books?”1 as the author speaks to the difficulties of writing for kids in a way that will nourish and challenge them by understanding who they are and what they need:

I believe in the necessity of offering children versions of wonder. I don’t mean the twee commodified vision of wonder we’re sold – the Instagram post of a mountain lake with an inspirational quote. I mean real wonder: the willed astonishment that the world, in all its dangers and clumsiness, in all its beauties and miracles, demands of us. Active, informed, iron-willed wonder is a skill, not a gift: you have to work at it. And you cannot remain in awe of that which is familiar, so the only way to maintain wonder is to learn: learn, and keep learning.

I have a hard time believing that the creators of iPad games and YouTube slop for kids have similar principles in mind. And even when kids do get to read, the things that are being created for and marketed to them are, like everything else these days, missing that essential spark of wonder. Sondra Eklund, a book reviewer and children’s book procurer for a library, describes the onslaught of (you guessed it) AI-generated content on the children’s book market, which she experienced while trying to acquire some books about animals for her library’s shelves:

Here’s the page that first convinced me we couldn’t put these books on library shelves:

A rabbit has a male and female counterpart. A male rabbit is called a buck. The two types of rabbits have different characteristics. A doe is a baby rabbit, while a buck is a mother. All types of rabbits live underground, except for the cottontail, and their habitats are often called warrens.

Later, I read on. One spread has the same exact text on two facing pages. But the place where it got so bad it’s hilarious was the final spread:

If you’ve ever had the pleasure of feeding a rabbit, you’ve probably wondered how they reproduce. The answer is simple: they live in the wild! Despite being cute and cutesy, rabbits are also very smart.

They can even make their own clothes, and they can even walk around. And they’re not only adorable, but they’re also very useful to us as pets and can help you out with gardening.

It would be comical if the present and future it described and portended weren’t so bleak. How many busy and overworked librarians, parents, and elementary school teachers have the capacity to audit prospective purchases so carefully? How much straight up garbage passing as books is finding its way onto shelves? I’m not naive enough to think that children are held sacred enough in the death cult of capitalist society that no one would try to make money off of them through these blatantly anti-social practices, but it still rankles to see the end product in practice.2

Easy, then, to give in to despair. But if an end to the root of these problems is not possible short of a revolution that remakes our social order, this is one area where resistance feels possible on the home front. Of that practice, Rundell writes:

…the imagination is the primary and first site of resistance. The market abhors all values that are not the values of the market: children’s books, to a great extent because they are written for those who cannot participate in the market, can offer resistance to a vision of the good life which is a built on a hegemony of acquisition. Children’s books insist in having faith in vast truths that lie beyond consumption and display. Their utopianism is that of the Moomins and Pippi Longstocking: it offers an experiential microcosm of a more ideal world.

I don’t have kids of my own, yet. But I do feel a strong sense of responsibility to the kids in my life. My nieces and nephew, my friends’ babies, the kids in my neighborhood and on the middle school flag football team I’ve been helping coach. That responsibility is one that includes the more obvious acts of care—love, affection, learning, safety—and the less obvious, like trying to help them cultivate an active sense of wonder. Or, rather, to help defend their innate sense of wonder against the intrusion of the loud, capitalist world that would gladly destroy it in exchange for targeted ad revenue.

The garden is a good place for this. More secluded nature spaces, too. But maybe it all comes back to books, which can have such compounding, expansive effects on the minds of kids. Even if the joys this practice leads to for them are simple ones, like a radish sandwich, well—that still feels like plenty.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

Rundell also includes the following backstory, of which I was unaware: “Food gives both solid reality and delicious longing to children’s books. Brian Jacques, author of the Redwall series about monastic chivalric mice, was a milkman when he began volunteering to read at a school for the blind. He found himself horrified by the quality of the books he was reading, and decided to write his own – and, because the children were blind, he accentuated senses other than sight: smell, sound, temperature, texture and, most important of all to children, taste. The food in Redwall is the thing most of its readers remember: it gives the story the rich shine of desire.”

Another “fun” case in point here is Roman Sandler’s Under the Rockets’ Glow, a children’s book written to explain and defend the Zionist position to kids amidst Israel’s genocide in Palestine, the kind of book you can only write if you don’t see the children living a scant few miles away from you as human. The book is blatantly illustrated by AI, which is a nice little encapsulation of our current moment, and Sandler himself is by day an AI developer with Nvidia, which just inked a $500 million investment deal in Israeli AI R&D. Charming.

Since I teach books to kids every day, I encounter this lack of “wonder” all the time. Usually the curriculum (and I, too) read a book to teach some specific point: this is what we should do, this is what we shouldn’t do, this is how this works. It’s astounding when I end up going off script and reading something like “Where the Wild Things Are”, and then suddenly all my usual prompting questions fail. I just end up asking: “…well, what do YOU think?” and just let them talk, because it’s not trying to make some specific, hamfisted point. It’s just wonderful.

Especially loved the shoutout to the Redwall books, they were dear to me growing up and remain so–as I reread them with my 10-year-old nephew they hold up pretty well, though I will say that I find the way that Jacques splits the various types of animals into binary categories of "naughty" or "nice" quite troubling.